Racing improves the breed.

It’s the second most cliched saying about motorsport after ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ – but is it actually a cliche?

While most motor racing has moved far away from production crossover, Formula 1 cars have more in common with a spaceship than what you’ll find in your showroom and even Supercars are so removed from production cars that it needs the new Gen3 rules to bring some semblance of what we can drive on the road.

But there is one series, and one race in particular, that not only has a long history of innovation that has been applied to road cars, but is still helping evolve what we drive on the road – the 24 Heures du Mans.

Le Mans is on this weekend so what better time to look back at some of the technologies and concepts that were developed in the twice-around-the-clock sports car race that have shaped the cars we drive today.

Le Mans is arguably responsible for the concept of sports cars as we know it, because it was the opportunity to showcase a car company’s ability to build both a fast and reliable car that led the likes of the Bentley Speed Six and Alfa Romeo 8C back in the earliest days of the race in the 1920s.

By the 1950s we had the likes of the Jaguar XK-120 and Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing, then as the race progressed so did the cars. The 1960s gave us the likes of the Ferrari 250 LM and then Ford upped the ante with the original GT40. By the 1970s the race had turned into more of a prototype contest but it continued to find ways to ‘improve the breed’.

Disc brakes

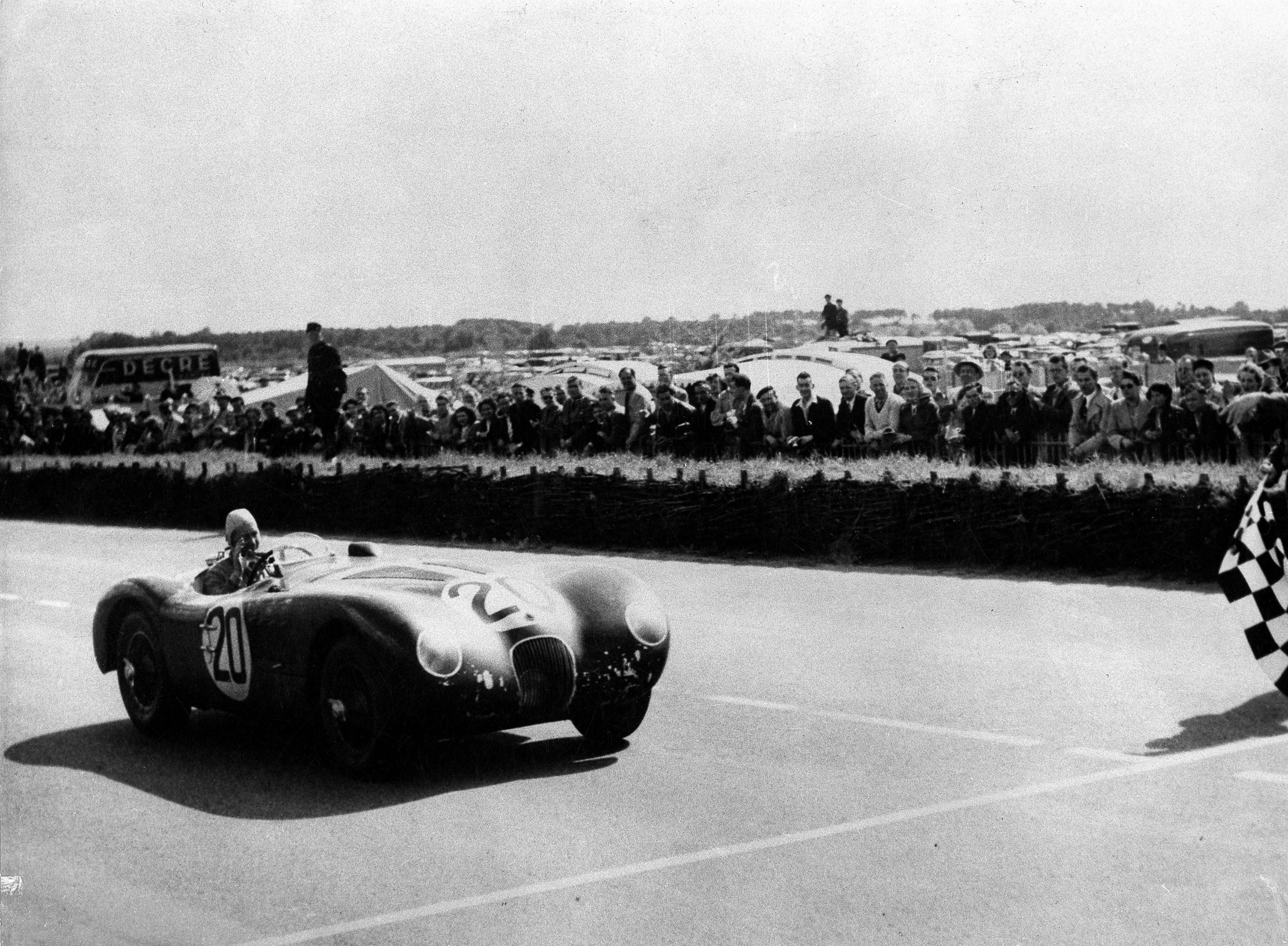

Jaguar helped advance the cause of disc brakes with its victory at the 1953 Le Mans race. The C-Type driven by Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton was fitted with the then-experimental disc brakes. Not only did they win the race, but did so in record pace with an average speed above 100mph (160km/h) for the first time in the race’s history.

It demonstrated the superiority of discs instead of drum brakes and within a few years all of Jaguar’s Le Mans competitors were using them and then began rolling out on Jaguar’s production cars; the 1957 XK150 was the first to have disc brakes all round as standard.

Turbocharging

The turbocharger was invented way back in 1915, before the first Le Mans 24-hours in ‘23, but it was at the French race that really demonstrated their potential. Porsche began experimenting with turbocharging its 917/30 but the gamechanger was the ‘74 911 RSR Turbo which finished second at Le Mans.

Porsche fine-tuned the engine for the ‘76 Le Mans winning 936 prototype and within a few years the 911 Turbo was a staple of the German brand’s road car line-up. With the reliability and performance benefits of the turbocharged engine demonstrated at Le Mans it became commonplace on performance cars from then on in.

Dual-clutch transmissions

One of the side effects of the turbocharged engines was the lag created when you changed gear and needed the turbo to come back on boost. So, Porsche began developing a new type of transmission that could reduce turbo lag but having the next gear engaged before you even selected it.

That required two clutches, one to take care of the even gears and another to look after the odd numbers, so the next gear could be pre-selected – and thus the modern dual-clutch transmission (DCT) was born. Porsche developed the DCT through the late ‘70s and early ‘80s before debuting it on the ‘86 962C Group C prototype that won Le Mans that year.

It took a long time for this type of transmission to filter down to road cars with the first mass-produced model with a DCT being the 2003 Volkswagen Golf. Now they are far more common, particularly in performance cars including Porsches, naturally.

Performance diesel

Diesel technology wasn’t invented at Le Mans, but Audi’s domination of the race with its turbo diesel powered R10, R15 and R18 TDI prototypes in the early 2000s made it a performance option.

Until then diesel was seen purely as a choice for those who wanted to save at the pump, but the V10, V12 and then V6 engines demonstrated that the torque-rich characteristics of a turbo diesel worked for an exciting and fast car too.

Audi launched the SQ5 TDI at Le Mans in 2012 to emphasize the connection and since then potent diesel-powered SUVs, sports sedans and even the occasional hot hatch have become showrooms regulars.

Performance hybrid

In the same way Audi made diesel a performance option, so too did the hybrid era of LMP1 regulations make electrified performance an appealing proposition. Hybrid road cars already existed by then, but the Toyota Prius was hardly an exciting or fast car, but by the end of the hybrid LMP1 era the world had been blessed with hybrid supercars including the Porsche 918 Spyder, Ferrari LaFerrari and McLaren P1.

The credit for the first major racing experiment with a hybrid car at Le Mans must go to American boutique manufacturer, Panoz, which brought a hybrid version of its front-engined GT racer – dubbed ‘Sparky’ – to the race in 1998.

It didn’t catch on then, but when Toyota returned to prototype racing in 2012 it did so with the TS030 Hybrid, which paired a V8 engine with a kinetic energy recovery system (KERS_ to provide a power boost while saving fuel. Audi countered with its R18 e-tron quattro, a diesel-electric hybrid and the rest is history.

Discussion about this post