Plug-in hybrids were yesterday’s news, a ‘bridging technology’ that was simply inferior to all-electric cars and therefore redundant.

That was the attitude of many car brands only a few years ago, but fast-forward to the end of 2025 and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) are all the rage. In fact, the resurgence of PHEVs was the comeback story of the year, defining not only what we drove in ‘25 but shaping what we’ll drive in 2026 and beyond.

Overall PHEV sales were up over 125 per cent in 2025, with the country on-track to buy more than 50,000 vehicles powered by the technology.

A large reason for the second coming of PHEV is the influx of Chinese car makers, which focuses on what they call ‘new energy vehicles’ – PHEVs and electric vehicles (EVs). This is because the Chinese industry has been able to use electrification to catch-up to the rest of the automotive world.

While the MItsubishi Outlander was an early adopter of PHEV tech, it has been the likes of the BYD Sealion 6, GWM Haval H6 GT, Jaecoo J7 SHS, MG HS Super Hybrid and others that have helped PHEV sales really take-off again. In 2025, Australians are likely to buy more than 30,000 PHEV-powered SUVs alone.

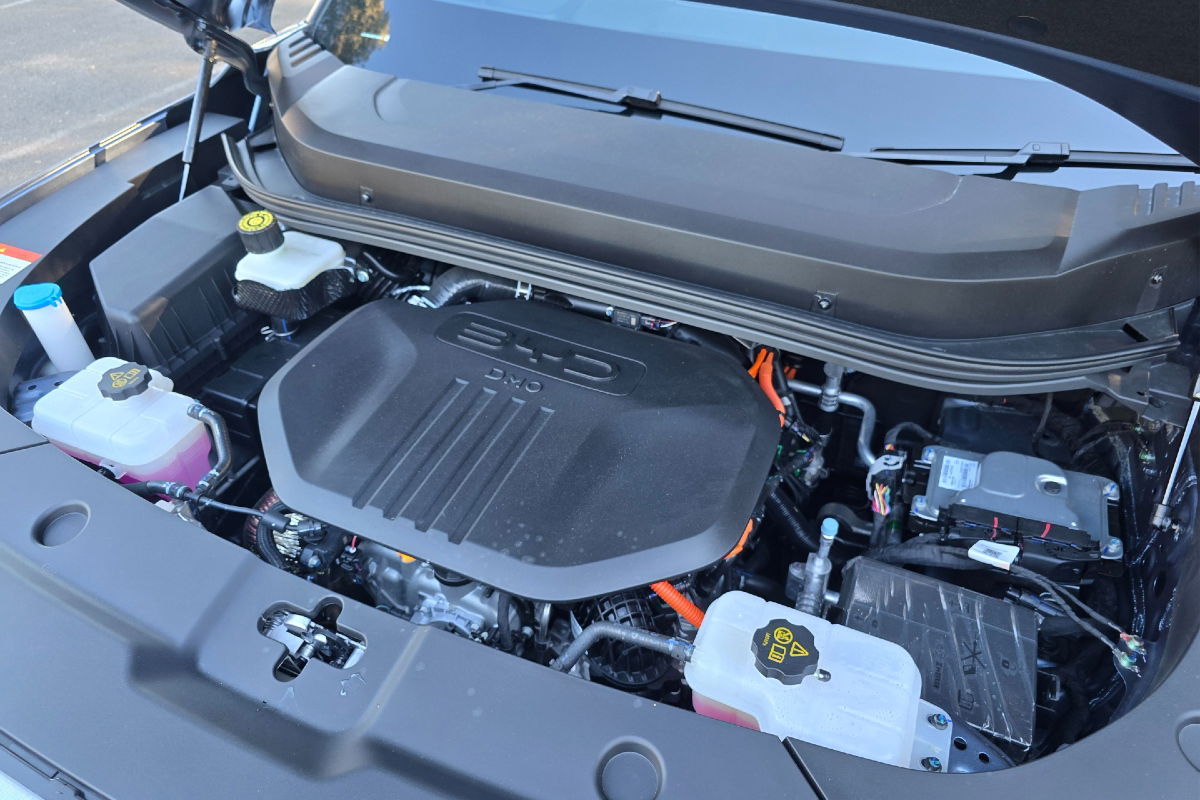

Then there’s Australia’s favourite type of vehicles – utes. While it remains dominated by turbo diesel power, the arrival of the BYD Shark 6 in late 2024 has changed the market radically. The Shark 6 has since been joined by the GWM Cannon Alpha PHEV and Ford Ranger PHEV (plus the Ford Transit Custom PHEV), which has seen light commercial PHEV sales grow to approximately 20,000 in ‘25.

Two years ago, there were zero PHEV utes and the total PHEV sales were just over 11,000, so it is clear that the technology has found a new audience and has a potential future.

And you don’t have to believe me? Having ignored the technology for years (and forsaking its leadership in the hybrid space) Toyota is set to introduce its first PHEVs in ‘26. Toyota is only in the business of selling cars that people buy, so if it believes there is long-term potential for the technology.

Most other major brands have already announced plans for PHEV additions in 2026, with vehicles as diverse as the new Denza B5 SUV to the Volkswagen Transporter van.

The reason for this revival is largely two-fold. Firstly, the technology has improved and made PHEVs more appealing to customers. Early examples had a very limited electric-only driving range, typically less than 50km, whereas the latest examples are closer to 100km or even beyond. This makes them more usable for daily electric-only commuting, or just generally improves fuel economy.

Secondly, the introduction of the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard by the Federal Government makes PHEVs a major help for car companies looking to meet the emissions targets. That’s because PHEVs return very low fuel consumption and CO2 emissions numbers on the testing cycle.

Another factor is the on-going acceptance of EVs, which have gone from oddities to genuine mainstream options for many buyers. But for those looking to cut their fuel bills but without wanting to spend the bigger money typically demanded by EVs, a PHEV is a nice alternative.

So expect to see PHEVs become a more common sight in 2026 and beyond, because this comeback technology looks to have plenty of life left in it.

Explainer: What is a plug-in hybrid?

If a conventional hybrid system uses the internal combustion engine to primarily drive the wheels and relies on an electric motor and small battery for assistance at select times, a plug-in hybrid is typically the reverse.

The electric motor (or motors) drive the wheels and the petrol engine is there to help act as both assistance or an energy generator for the battery.

Plug-in hybrids tend to have larger batteries than a conventional hybrid but smaller packs than an all-electric car – which allows them to be cheaper than an EV.

The advantage of a PHEV is the option of zero-emissions driving for short periods (less than 100km) but with the option to fill up with petrol when needed and take longer trips like a conventional petrol-powered car.

The downside is, if you don’t regularly charge the battery you will end up using more fuel because you’ll be either using the engine to charge the batteries or relying on the internal combustion engine to do all the work.

Discussion about this post